If there is one thing that can save a miserable child’s life, it is a good teacher.

Born and bred an atheist, Festus McGillicutty never managed to avoid serving my ultimate purpose of love. It goes to show. I don’t have much to say about what people believe, or how they talk about me. I’m not going to be insulted by human opinion. However, I do hope and expect that people will follow a religion of goodheartedness, and that is what Festus did his whole life long.

The night he found Ellen on the highway, Festus was returning to Howey Bay from a trip to the neighbouring town of Four Foot Falls. It was the only place in the vicinity of a hundred kilometres where a person could find a Big Mac, and every week he made the drive to reassure himself that he still lived on the cusp of civilization.

At twenty-seven years old, Festus felt alive, aged, and wise. The previous summer he’d left behind his parents, a boisterous set of eight siblings, and a long-time sweetheart on the east coast to start a teaching job in northern Ontario. He didn’t know quite why he’d done it. Probably to escape the settling down which had begun to feel inevitable.

One day he had looked into the sharp green eyes of his high school sweetheart, a young woman named Carole, and knew it wasn’t his desire to spend the rest of his life with her. Something about the way she smelled, or her hawkish nose. But there she was pressing, nudging, doling out hints that became less and less subtle as time went by. The woman, kids, life, time . . . all of it was occurring too fast, without his permission.

Festus arrived in Howey Bay in August, when the mosquitoes had settled down and the sun was still hot. Nice place, he thought, but pretty small. Rocks and trees and trees and rocks, and water. Maybe he would only stay a year.

Then the leaves began to turn. Within two weeks, the rugged cliffs of the Canadian Shield were awash with blazing oranges and yellows, rippling upon brown lake water. During his Big Mac drives, he shared the highway with wolves, bears, martins, foxes, and moose, all of them regarding him with a challenge in their amber eyes.

The first winter smacked him upside the head and spun him around till he was dizzy. The sheer sparkling force of the season numbed and delighted him. He got frostbite three times, learned to cross-country ski, and bought a snowmobile. He made friends with every teacher at Howey Bay Elementary; he was teaching Grade Three. He became known as the funniest and handsomest bachelor in town. In spring, wearing his trademark red baseball cap, he attended the Northwestern Ontario Trade Show and snacked on moose sausage and bannock. There he made the acquaintance of Miss Tara Willows, the pretty administrative assistant for Howey Bay Real Estate. She had a tiny waist, red lips, and a grey pea coat that swirled around her knees. She’d grown up here; her father was the local magnate, if anyone deserved the title in this humble place.

Maybe he would stay on longer than a year.

Festus wasn’t awfully surprised to see an adolescent girl hurrying down the highway, close to the town’s entrance. Hitchhiking was common practice in these parts, and safe to boot. There was no local bus service between Howey Bay and Four Foot Falls, so anyone lacking a ride could stick their thumb out and chance had it they’d be picked up by an acquaintance.

Festus was taken aback, however, when Ellen bent down to his open passenger window and showed her solemn face. She was young, a child. The whole way home, he lectured her on the dangers of the highway, listing all the sharp-toothed animals he’d seen only in the past few months. The girl folded her hands in her lap and nodded mutely. She held herself distant. He dropped her off at a house near the mine just as the whistle blew, and drove away.

The next September, following a long golden summer of canoeing and wooing the lovely Miss Tara, Festus McGillicutty walked into the grade seven classroom at Howey Bay Elementary. He’d never taught pubescent children before. How was he going to stem the tide of hormones cascading through this small, stuffy space? He coughed nervously and looked out at his class.

There they were, arrayed in rows. Some of them glanced at him, some were absorbed in their peers. Front and centre, talking animatedly to a classmate, was the little hitchhiker he’d picked up one night last spring. Her dark hair fell in long ringlets past her shoulders, and she used her hands as props to exaggerate her words.

“No, seriously,” she was saying. “My parents thought I’d become a hermit . . . It wasn’t just you! I didn’t see anyone all summer. Nope . . . No, it wasn’t lonely. Are you kidding? It was bliss! The only thing anyone wants to do around here is watch television. But I go outside. I’m an explorer, an exploring hermit. You should’ve seen how many dead animals I found. Have you ever watched a decomposing animal? You have to hide it, of course, or it’ll get eaten. It’s educational, you should try it. Nothing like a skeleton to get you in touch with your own mortality . . .”

Festus McGillicutty read out the roll call.

So – this was Ellen Romper, subject of many a staffroom discussion. He studied her long face and queer eyes subtly. Her voice was loud and often punctuated with brash laughter. She seemed less pale, less anxious than the night he’d picked her up. She gave no sign of recognizing him.

Festus cleared his throat and gazed out over his students, light streaming through the tall windows. The class reminded him of an active pond, rippling with insolence and creativity; he saw their faces, some upturned, some downcast, children’s faces still, yet slipping over the edge of self-awareness into young adulthood. He imagined them as little tadpoles sticking their glistening heads out of the water. They would kick their newfound legs, but their tails had yet to recede.

Over the intercom, the principal’s voice beckoned everyone to sing the national anthem. The grade sevens stood up awkwardly, mumbling the words. Festus felt mortified for them. Why should they have to get up and utter these words of antiquarian loyalty to the state? Was this the purpose of education – to form a child’s sense of national identity? He didn’t think so. Education was about questioning, about engagement, about response. When he’d taught the grade twos and threes, he’d always appreciated their enthusiastic participation in the anthem. They sang it out of robust choice. They still believed in the magic of everything, at that age.

Now, as he observed how the boys blushed and fidgeted, how the girls twisted their thumbs and stared vacantly at the clock, Festus felt indignant. It was a form of brainwashing, that’s what it was. He sighed. Now came the Lord’s Prayer. Of all things, this morning ritual of the elementary school system made him feel most like calling in sick.

You know, Festus was right on that count. What on earth do I have to do with public education? School should be a place where children learn about the world and its goings-on. Reciting ancient supplications to the male godhead of a certain religion distracts the children from my original purpose, which is merely that they grow in understanding and wisdom.

“Do not say this if you don’t know what it means,” Mr. McGillicutty instructed. His lip curled.

The students looked at him in astonishment.

“Does anyone believe these words, or know what they mean?” he asked.

No one did, except Ellen, who described the prayer as my basic requirements. She was the lone churchgoer in her class; all her Mennonite friends were homeschooled by their mothers.

The majority of the grade sevens opted to refuse the prayer, feeling like renegades. This granted Mr. McGillicutty an instant win on the playing field of respect. Ellen, however, spoke it aloud, all the more reverent next to her hellbound peers.

Following the morning announcements, Mr. McGillicutty prompted, “Has anyone heard of the USSR?”

Several hands fluttered up.

“It’s an empire.”

“Russia.”

“A communist country.”

“In this classroom,” Festus continued, “USSR means Uninterrupted Silent Sitting & Reading.”

“AWWWWWWWW,” went the whole class.

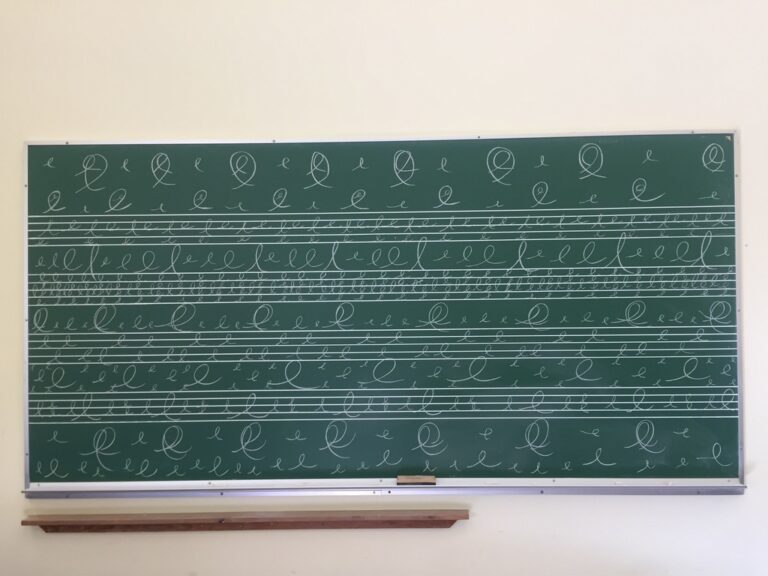

“What about the and? It should be USSAR,” a voice piped up. He recognized it as dark-haired Ellen’s. Without answering, he turned and wrote the words on the blackboard, using an ampersand symbol to denote the conjunction. She was quiet.

The children each chose a novel to read. Then they spent fifteen minutes journalizing. A layer of calm satisfaction descended on the room, punctuated by the odd complaint here and there. Festus perambulated the rows of desks, feeling somewhat triumphant. This wasn’t going to be too difficult after all. They were still children, which relieved him; they still possessed spirit, naivete, instinct. It would do these kids good to get inside their own heads, find out what was going on there.

As he walked by Ellen’s desk, she suddenly poked her freckled nose above her book, raised her eyebrows high, and whispered, “Hello again!”

If it weren’t for Festus McGillicutty, who in Geography threw the globe around like a basketball, Ellen would have found grade seven utterly demeaning. Suddenly the boys wanted to kiss her mouth and hold her close during slow dances; it made her tremble and gag. They smelled like French fries drenched in cologne, their lips were wet. The girls had become jealous and catty, together forming a seething concentric formation like a mass of penguins attempting to survive an Antarctic winter. Ellen never knew when she would be sucked in or pushed out of the warm inner circle. Every day, she woke up steeling herself for the next bicker with Pammy, who, in all her cheery power, could turn the entire classroom against someone in the span of time it took to eat a sandwich. Sometimes, though, Ellen found herself rewarded unexpectedly with sweet notes expressing a profound declaration of friendship, the i’s all dotted with fat little hearts.

If her social life wasn’t uncomfortable enough, Ellen found herself beholden to peculiar moments of anxiety each afternoon at school. Like clockwork, at 2pm, her heart began fluttering, her chest seemed to cave in, her hands shook, her feet tingled, her eyes shrank, her whole body shuddered into a spasm of emotional panic. She started to giggle or whimper, wringing her hands and grimacing like a monkey; then she put her head down on the desk, gulping air. The other students snickered into their hands, but the joke was not under Ellen’s control. After an attack passed, she felt tired and wan.

Festus McGillicutty recognized these bouts as panic attacks and secretly wondered about Ellen’s home life. He felt the girl’s exhaustion; her face became transparent and unsteady, the way the long icicles hanging down from the eaves of the school would shiver into water in the sunlight.

“Come back to us,” he would say when she started to melt down. “Where are you right now?”

“I don’t know, I don’t know,” she moaned, face buried in her hands. A cold, clammy smell rose off her body.

He knelt down in front of her desk. Policy dictated that he wasn’t allowed to hug her, which was what she needed, so he just placed his hands on the top of her shoulders.

“Look at me, Ellen.”

She shook her head.

The other students gaped, puzzled, incredulous, jealous. Pammy whispered something sideways to Cammy. They both opened their eyes wide at one another.

“Everyone, back to your work.”

A busy shuffle ensued.

“Ellen,” he said quietly.

She took her hands away from her face and saw the big, dark, caring eyes of Festus right across from her. He was very warm; he drew her away from something inside that made her anxious and shrivelled. Her cold fists floated down onto the desk, and his warm hairy hands gripped them.

“Where do you go, when you’re in there?” he asked. He was conscious of his twenty-five other students, their needs, the time, the imperative that Ellen get back to her learning.

“Nowhere, nowhere,” she said, almost crying. “I don’t know.”

“What do you need?”

“I need . . . I need . . .” She took a breath. “I need to be alone.” She felt the cruel ignorant eyes of all the other classmates on her and knew they did not, would not ever understand and that was why she continued to try to explain everything, to no avail.

The school nurse and Marisol together arrived at the conclusion that Ellen was experiencing low blood sugar effects. She would start bringing yogurt-covered raisins as an afternoon snack. When she ate a few of these little “pills,” the shrinking feeling seemed to subside, but not without some kindly words from Mr. McGillicutty.

In the mornings, she arrived at school like a pharaoh riding a chariot. Her voice commanded the whole room. “Who here does not like bowling? If you do not like bowling, you cannot be my friend. I went bowling last night and scored all strikes, except one. The last one was a spare. I’m going to be the owner and proprietor of a bowling alley – the biggest, most prestigious bowling alley in Howey Bay. Better line up to pay your admission fees now. Or you’ll never get in. I’ll be like God, and my bowling alley will be like heaven. Lanes paved with gold. Only those on the straight and narrow need apply. So I guess that leaves out all of you! Ha ha ha!”

“My sister’s cat was lost for at least five days. She cries constantly. I think it’s dead. I hope it’s dead. We had a fight last night, she scratched me on the face with her fingernails, so I wrote on her whiteboard . . . ‘i hope your cat is dead.’ Then this morning her stupid high school friend goes, ‘Hey was that your cat lying on the side of the highway?’ Can you believe it!? Ha ha ha. It’s like I’m a prophet. I always knew I was a prophet. Ha ha ha!”

Festus knew he couldn’t trust the way Ellen acted with her friends. She was too loud, her confidence flashing like a shield against the world. Instead, her morning journals became his window into her thoughts. She wrote of the strife between her parents, hatred of a certain brother, wanting to be alone. She described her dreams, which were always of small animals she collected up with wheelbarrows and scoops and hoses. She wrote all about Leander, who snuggled in her lap every morning and night, who loved her with his whole heart.

To my horror, she also glowed with praise for Jesus and me, exhorting Mr. McGillicutty to accept the love of Christ and abandon his path of wickedness. It bothered her that his good soul might rot, what with his open confessions of atheism and his evident dislike of the Lord’s Prayer. He gave her low marks when she wrote that type of thing, and asked her piercing questions about her own free will.